This image, “balance scale” is copyright (c) 2011 winnifredxoxo, adapted, and made available under a Attribution 2.0 Generic License

Rebalancing a portfolio is essential to maintaining the risk profile that you originally set for your portfolio, and can actually improve the performance of a portfolio compared to if you never rebalanced at all. This article discusses what it means to rebalance a portfolio, why you should do it, and how to do it.

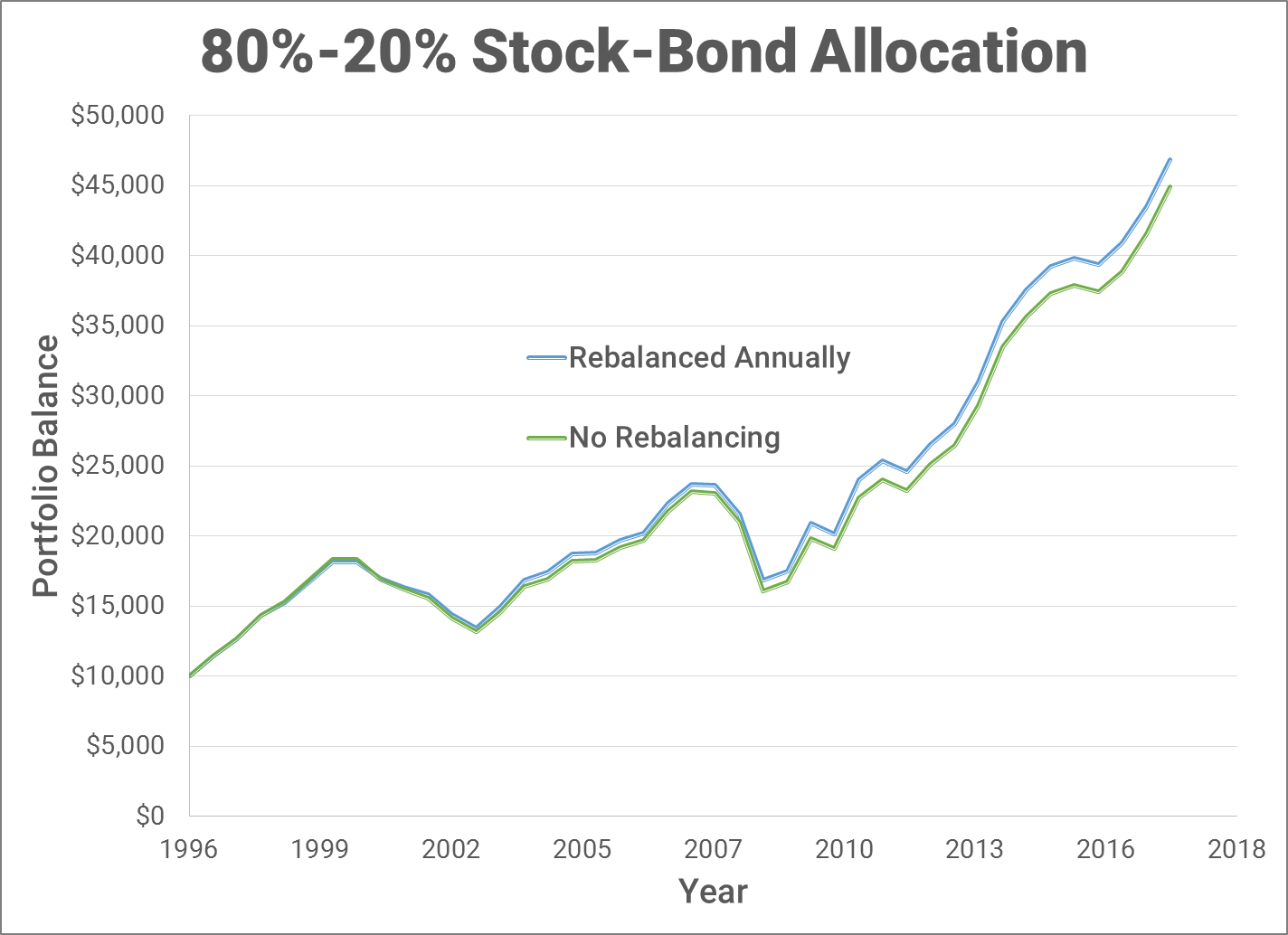

Shown below is an example of a portfolio that is 80% allocated to US. Stocks and 20% allocated to U.S. Bonds. The portfolio starts with $10,000 at the beginning of 1997 and the performance is charted over the course of 20 years until June 30, 2017. All values were obtained using Portfolio Visualizer, a free online tool to simulate any sort of portfolio. The blue line shows the performance of the portfolio if it is rebalanced annually, while the green line shows the performance without rebalancing. The purpose of this graph is to show you that the performance of an annually rebalanced portfolio can beat the performance of one that is not rebalanced. If you look at the links below the chart, you will also see that the standard deviation (i.e. volatility) is also lower!

- Link: Portfolio Visualizer with Rebalancing

- Link: Portfolio Visualizer without RebalancingLink: Portfolio Visualizer without Rebalancing

What does it mean to rebalance your portfolio?

In a previous article I discussed how to create a target asset allocation, which altogether represents your portfolio. When a particular asset class is significantly deviated from your target, then you may want to rebalance your portfolio so that it remains in line with your orginal target. I will discuss two options in the last section of this article; either of them will help rebalance your portfolio.

Why should you rebalance your portfolio?

Keep in mind the reason you created a target asset allocation in the first place. It should be representative of your risk tolerance as adjusted by the weight and risk of each asset within your portfolio. Lets pretend we started investing $100k with the following target asset allocation (hover over the pie chart to see balances):

Target Asset Allocation

Over time, the balances of each asset will fluctuate. In this example, the total balance increased by $20k, which could realistically happen in a 2-year span. The allocation could look like the following:

Unbalanced Portfolio

The increased performance in stocks as compared to bonds have now skewed your allocation to being more stock-heavy than your target desired allocation. This represents a portfolio that is riskier and more volatile than the one you had originally allocated. You may feel the urge to keep the higher exposure to stocks because it has been doing well, but it is well known that past performance is not a predictor of future performance. In order to tweak your asset allocation back to your original target asset allocation, you would need to rebalance your portfolio, which can be done in several ways. In the next section, I will go into more details on triggers for determining when to rebalance.

When should you rebalance?

1. Deviation Trigger

Of course the reason you would need to rebalance is because your portfolio has deviated from your orignal target allocation. Taking the example of our unbalanced portfolio above, stocks now represent 85.3% of the portfolio, but our target was 80%. Conversely, bonds represent just 14.7% now, but we wanted 20%. The important question is whether this is significantly deviated enough for you to do anything about it. The best thing to do is determine beforehand what your limits will be for rebalancing.

Absolute Percentage Deviation

You can decide an absolute percentage deviation past which you would rebalance. For instance, if your target stock allocation is 80%, then you would set the limits at 75-85%, which is +/- 5%. If the allocation is outside of this range, then you would decide to rebalance.

Relative Percentage Deviation

Similary, you can also set a relative percentage deviation. As an example, you can arbitrarily set a relative deviation of 20%. 20% of 80% is 16%, so a stock allocation outside of 80% +/- 16%, or 64-96% would trigger a rebalance. This is a huge range, and is a great example of the downside of using relative percentage deviations. However, this works well for assets with lower allocations. For instance, with the 20% bond target, 20% of 20% is 4%. This means that 20% +/- 4%, or an asset percentage outside of 16-24% would trigger a rebalance. This is a much more reasonable range.

In practice, using both absolute percentage deviation and relative percentage deviation, whichever range is narrower, is better for maintaining your target allocation. This can be applied to each asset in your portfolio. Alternatively you can also try this:

Percentage Ranges

Similar to the absolute percentage deviation, you can set a range for each asset in your portfolio outside of which you would rebalance. For example, you can specify a range for stocks of 75-85% and maybe bonds will be 6-14%. Of course if these are the only two assets in your portfolio, then in this example you would always deviate from the bond's range before the stock's. This strategy works better for a portfolio with 3 or more asset classes.

2. Timed Trigger

Timed trigger specifies a duration of time to wait between each rebalancing. This can be any time frame of your choosing, such as quarterly, bi-annually, annually, etc. Too frequent rebalancing and you could be reducing your exposure to equities in a bull market. Too long of a time frame and you risk your portfolio deviating greatly from your target allocation. Nobody suggests going longer than a year, however I think that annual rebalancing is optimal. Less than 6 months, your portfolio is less likely to deviate enough for it to matter. Additionally, selling assets held for less than one year in taxable accounts with capital gains will be subject to short-term capital gains instead of long-term capital gains, which is significantly more expensive.

How do you rebalance?

#1: Balance with New Contributions

All new money that you contribute to your portfolio goes to whichever asset class is deficient. For instance, here is my target asset allocation and my actual asset allocation at the time of this writing:

My Target Asset Allocation

My Actual Allocation

I am waaaay off (mostly because I have been throwing money into domestic large-cap index funds into my brokerage accounts since it is the most tax-efficient asset in a taxable account). If i were to follow this strategy, then any new contributions should go to a foreign index or REIT index.

However, when you are significantly deviated from your target and your portfolio balances are high enough, then it will be hard to rebalance your portfolio just by contributing more money. I have been pretty bad about reaching my target asset allocation this year, so Option #2 here I come.

#2: Buy Low and Sell High (Timed or Deviation Triggered)

This is when you exchange your overweighted assets for an underweighted one. Put another way, you are selling the assets that had grown proportionally more in the interim, and buying the ones that grew proportionally less (buy low sell high). This is best done in a tax-advantaged account, such as a 401(k), 403(b), or IRA. In these accounts, it doesn't matter if you are selling assets that have had signficant gains, since they will either never be taxed again (i.e. Roth) or will be taxed later at ordinary income rates instead. I do not recommend rebalancing within a taxable brokerage account unless it is part of your tax plan. I have some highly appreciated assets in my brokerage that I have held for 5 years. I could sell them now to rebalance, but I would have to pay long term capital gains tax PLUS net investment tax PLUS state income tax. Why pay for capital gains at my tax rate when I could reduce taxation with any of the following:

- transfer capital gains to someone else of a lower tax bracket (e.g. retired parent or child)

- hold the asset until a tax year in which I have a lower tax bracket, at which point I could sell or harvest capital gains (e.g. going part-time or fully retiring)

- hold until I have harvested capital losses elsewhere for which I can offset the gains

In the meantime, when I rebalance, I will keep all of my taxable brokerage assets as is, but buy and sell funds in my tax-advantaged accounts so that the total portfolio matches my target.